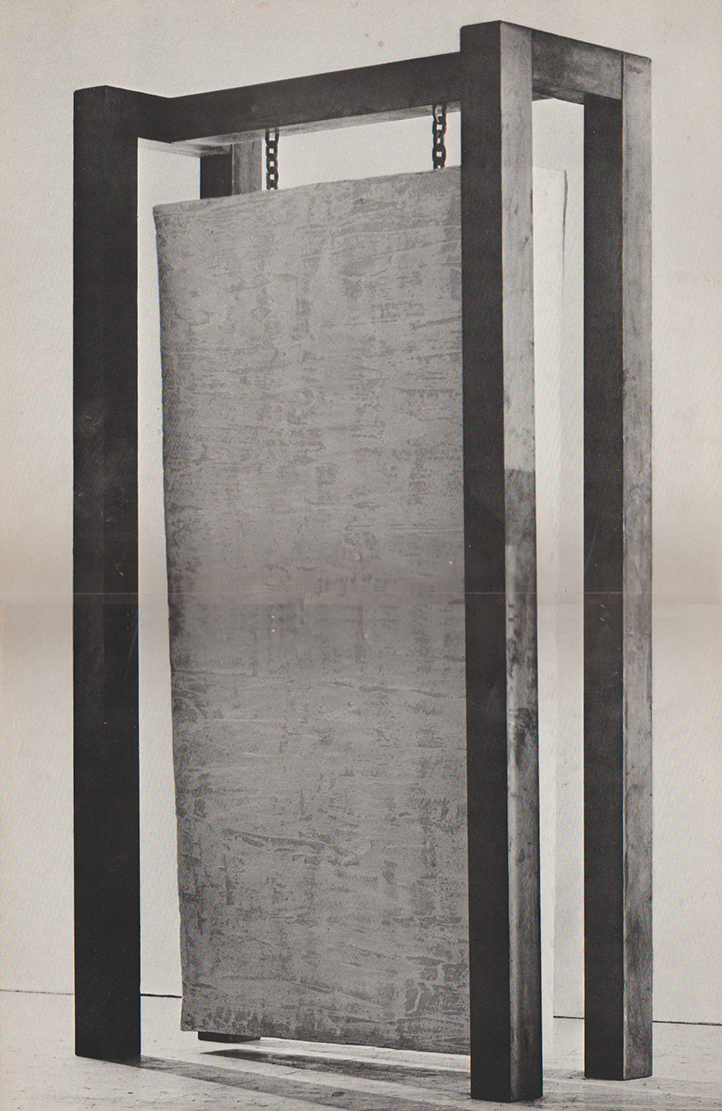

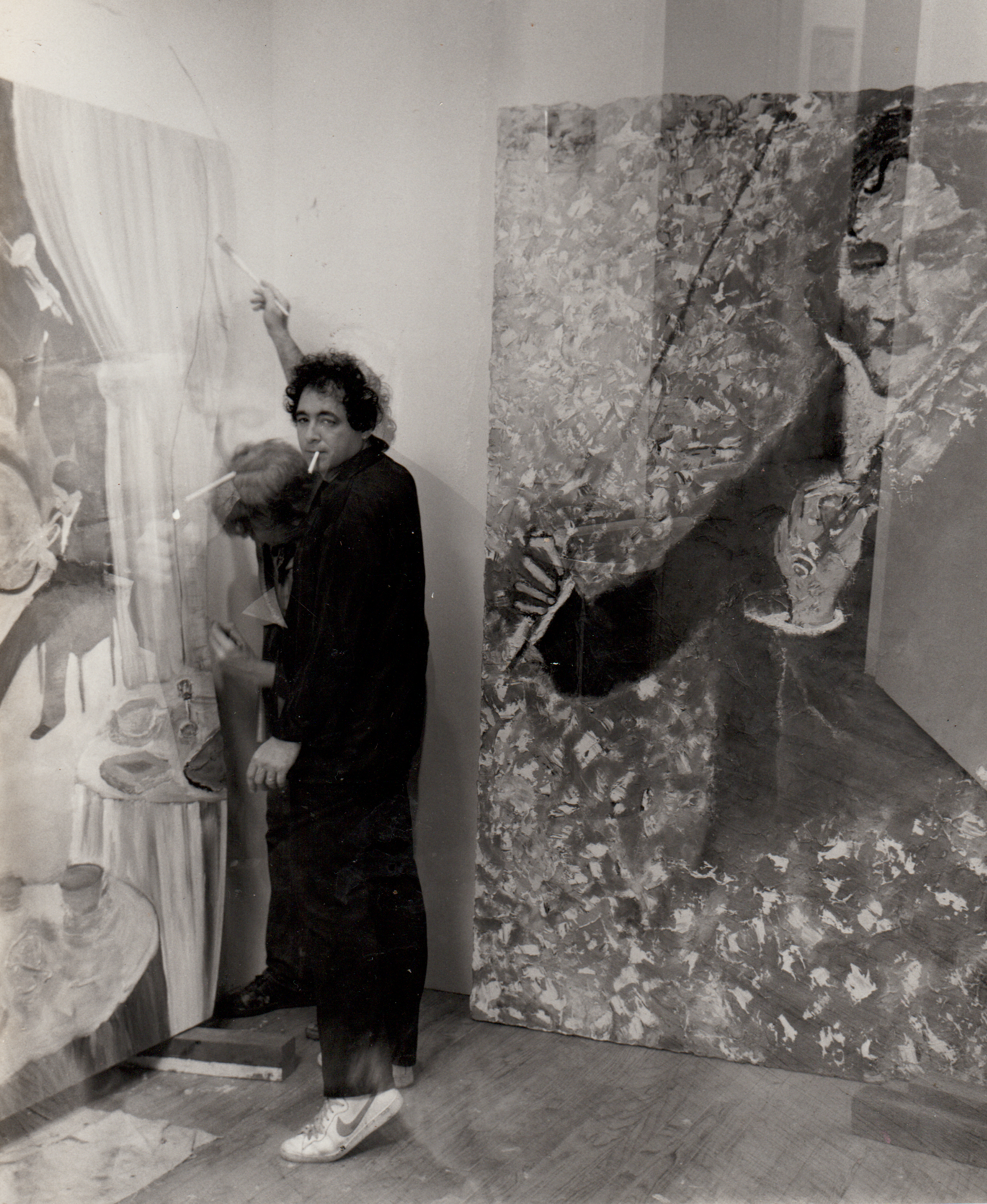

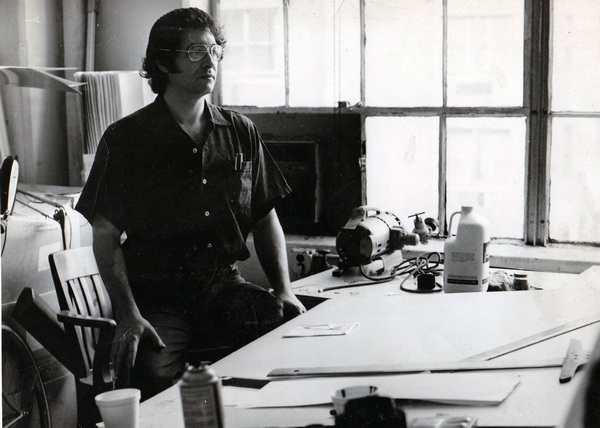

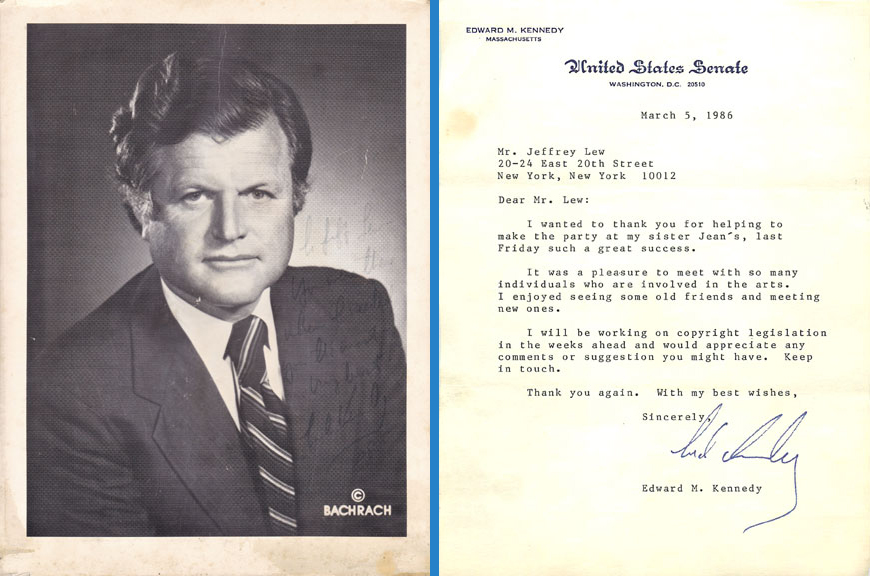

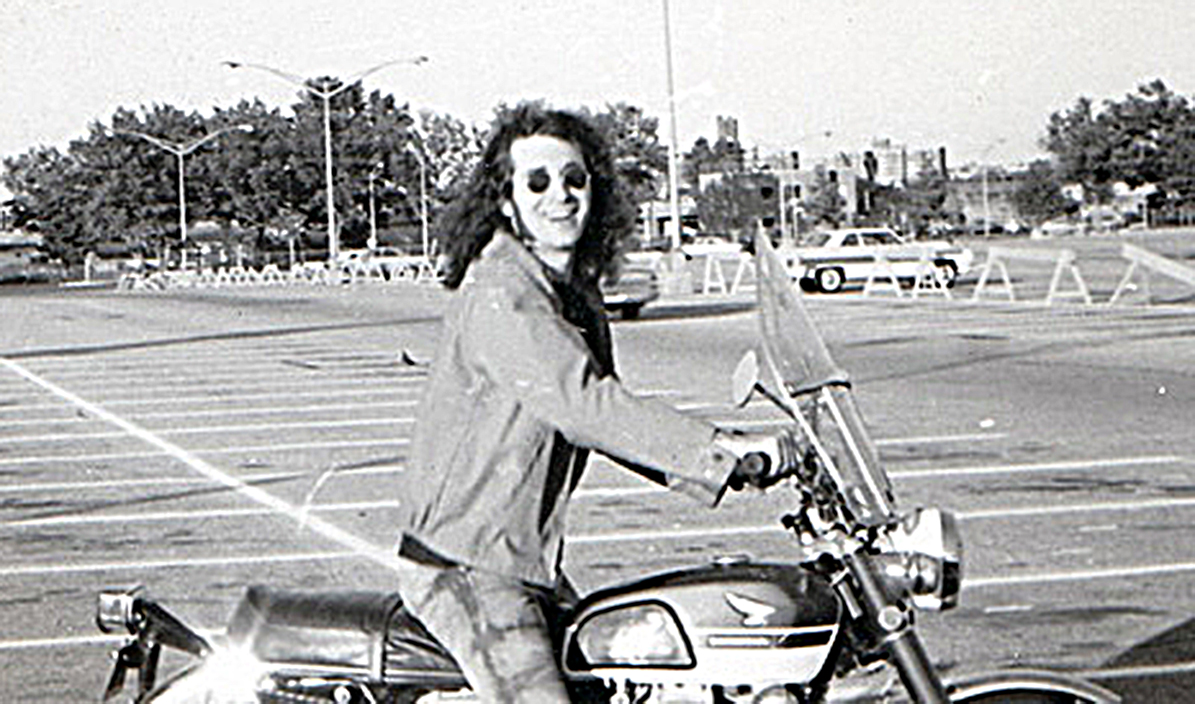

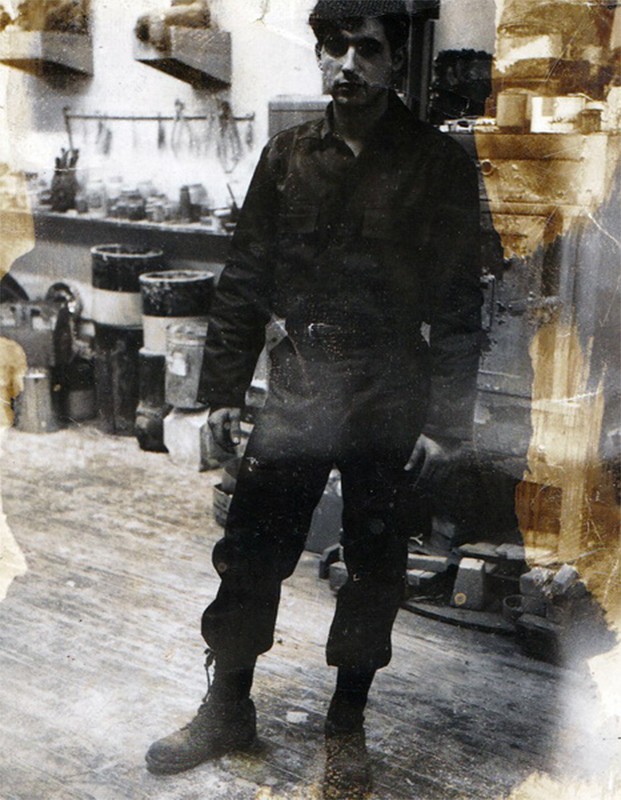

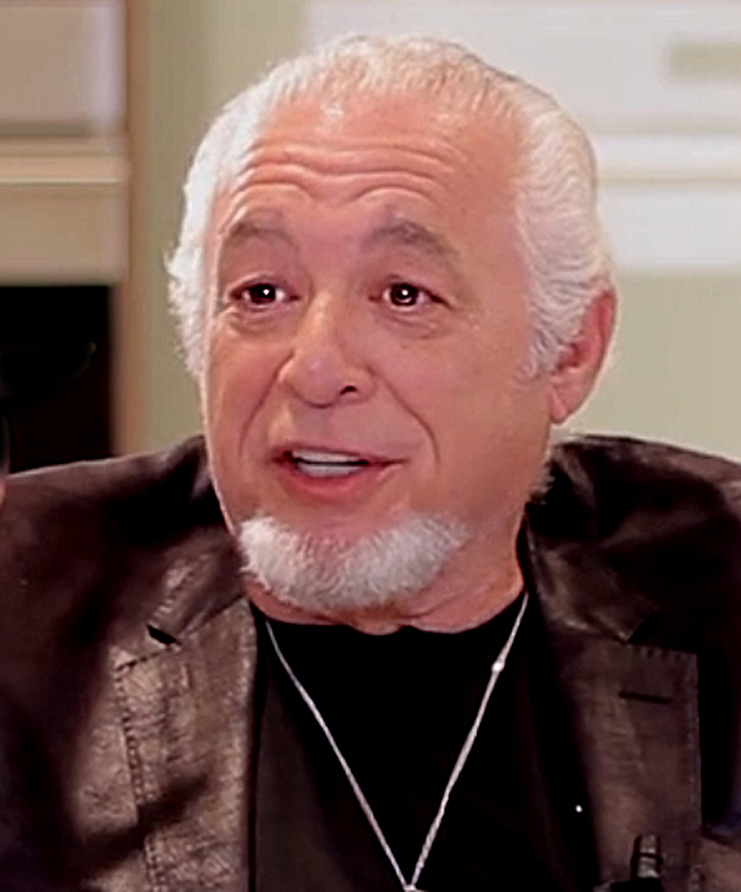

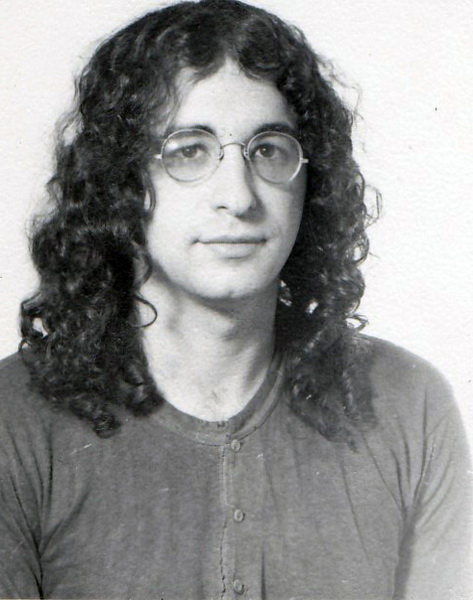

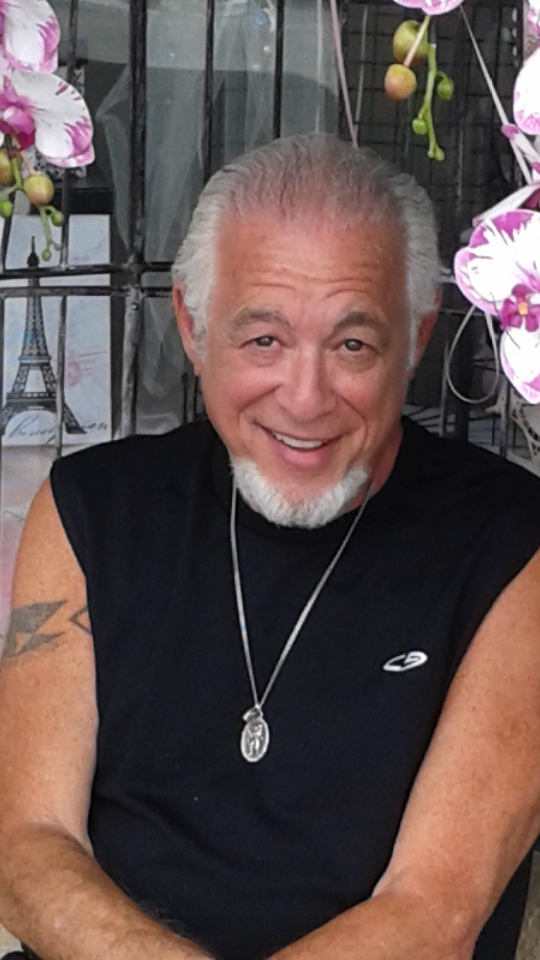

The year was 1970. It was a period of great freedom and experimentation in the arts. American artists were confident of their place in the international art scene as New York had become the art center. The cowboy image, that rough and ready attitude established by the Abstract Expressionists was confirmed and urbanized by the Minimalists through their use of industrial materials. With the emphasis on materials as well as scale, the lofts of Soho were found to be the ideal place to live and work. Jeffrey Lew bought the building at 112 Greene Street in the Soho district of Manhattan. The ground flOor was occupied by a rag factory, Soho was mostly light industry at the time, and when they vacated, Lew decided to let his artist/ friends use the space to make and exhibit art. There was a basement in addition to the ground floor totaling 8,000 square feet. "I invited Gordon Matta Clark and my other friends and they invited their friends." Jeffrey Lew recalls of the early days: "None of us were doing well then, we didn't have galleries. 112 was a place to show, a place to make art. The artists worked publicly, day and night, there were on-going shows. Most of the work was made right there. Shows didn't exactly open and close. It was continuous." So 112 Greene Street became a gallery, of sorts, a workshop for artists, and an alternative space, one of the first. It was supported in the beginning by Jeffrey Lew. Funds from the National Endowment for the Arts and the New York State Council oil the Arts came later. "What I did," recounts Lew, "amounted mostly to replacing light bulbs and washing the windows. I didn't fix the place up, but its nastiness was part of its appeal. I remember Max Hutchinson walking in one day, the New York Times in his hand. 112 had a half-page article and Max laughed and questioned why he had spent money cleaning up his gallery space when it seemed the way to get attention was to stay funky." Much of the aura of 112 Greene Street can be tied to this funkiness. The ar-tists were free to drag in all sorts of materials and to use the space itself. "Ya gotta stress funky!" says Jeffrey, "The place was big, dirty, dark, cavernous. And it had a sound, the beautiful sound of artists working." The stories are many. Charles Simmons covered the basement floor, all 4,000 square feet, with clay. Doug Sanderson dumped dry plaster on the floor and then drew in it. Jeffrey Lew took the metal plates that had served as walkways for the rag factory and welded them into a piece of sculpture which was filled with water. Gordon Matta Clark, using a jack hammer on the base-

ment floor, cleared away the concrete, exposing a patch of earth the size of a

room. In the center he planted a cherry tree, then placed a canvas on an easel

in this "studio". Jene Highstein punched holes in the walls and rigged pipes

wall to wall, low and wide, drastically altering the space.

The list of exhibiting artists seems endless. Susan Rothenberg and Ned

Smyth had their first exhibitions there, as did Mel Bochner. Carl Andre,

Rosemarie Castoro and Marjorie Strider had a floor, wall and window show.

Andre, of course, did the floor. Susie Harris built her flying machine and giant

pyramids, Richard Nonas, Tina Girouard, Susan Weil and Bernie Kirschen-

baum all showed in the early 1970's.

The place, the people, and the activities of 112 Greene Street have since

been woven into an art world legend. The stories are varied and often con-

tradictory so that now, in 1981, it is difficult to separate fact from fancy. One

thing always rings clear and that is what is commonly referred to as the

"spirit of 112". It grew out of the times, out of the general enthusiasm for art,

and out of the raw space which lent itself to experimentation. Jeffrey Lew

provided the space, the opportunity and did not interfere.

managed to divorce myself from my ego when it came to the censorship

of art. Well, nobody listened to me anyway. An artist would ask to show, I'd

say 'no' and the next day the piece would be installed. There were no commit-

tees, no censorship. It operated like a dance floor. When you were tapped on

the shoulder, you had to leave. The artists themselves had a way of dealing

with each other. If the artists didn't like you, they made it impossible for you

to stay. But mostly it flowed. There was a unique energy, a kind of life force in

the place, that kept things going."

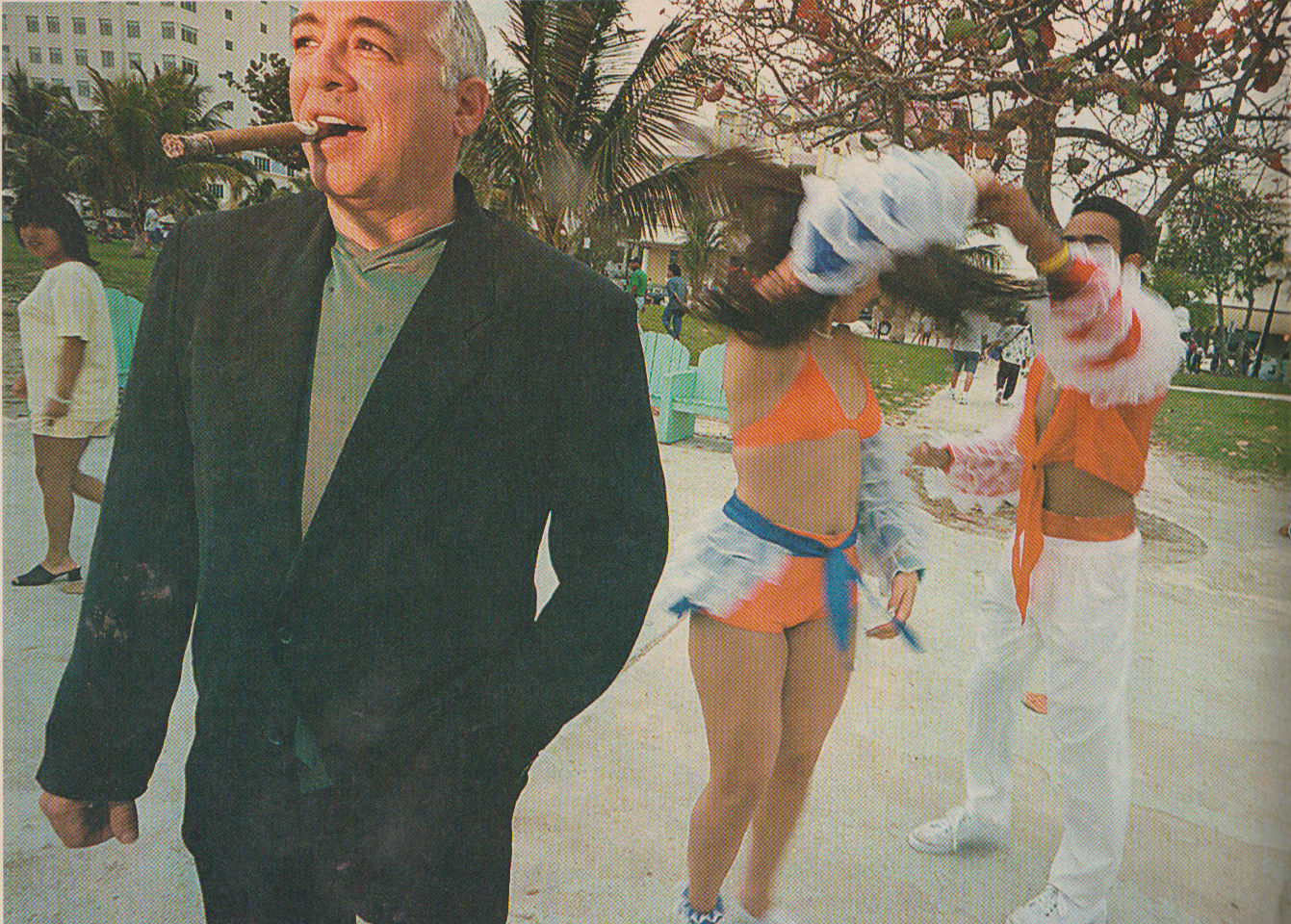

The original 112 Greene Street has evolved into White Columns Gallery,

located on Spring Street; Soho has developed into an art center of mostly

large, pristine spaces with white walls and polished floors. The artists who

survived the seventies are represented by commercial galleries, and the "112

Greene Street Revival" is a nostalgic look at something warmly remembered.

NANCY EINREINHOFER

ment floor, cleared away the concrete, exposing a patch of earth the size of a

room. In the center he planted a cherry tree, then placed a canvas on an easel

in this "studio". Jene Highstein punched holes in the walls and rigged pipes

wall to wall, low and wide, drastically altering the space.

The list of exhibiting artists seems endless. Susan Rothenberg and Ned

Smyth had their first exhibitions there, as did Mel Bochner. Carl Andre,

Rosemarie Castoro and Marjorie Strider had a floor, wall and window show.

Andre, of course, did the floor. Susie Harris built her flying machine and giant

pyramids, Richard Nonas, Tina Girouard, Susan Weil and Bernie Kirschen-

baum all showed in the early 1970's.

The place, the people, and the activities of 112 Greene Street have since

been woven into an art world legend. The stories are varied and often con-

tradictory so that now, in 1981, it is difficult to separate fact from fancy. One

thing always rings clear and that is what is commonly referred to as the

"spirit of 112". It grew out of the times, out of the general enthusiasm for art,

and out of the raw space which lent itself to experimentation. Jeffrey Lew

provided the space, the opportunity and did not interfere.

managed to divorce myself from my ego when it came to the censorship

of art. Well, nobody listened to me anyway. An artist would ask to show, I'd

say 'no' and the next day the piece would be installed. There were no commit-

tees, no censorship. It operated like a dance floor. When you were tapped on

the shoulder, you had to leave. The artists themselves had a way of dealing

with each other. If the artists didn't like you, they made it impossible for you

to stay. But mostly it flowed. There was a unique energy, a kind of life force in

the place, that kept things going."

The original 112 Greene Street has evolved into White Columns Gallery,

located on Spring Street; Soho has developed into an art center of mostly

large, pristine spaces with white walls and polished floors. The artists who

survived the seventies are represented by commercial galleries, and the "112

Greene Street Revival" is a nostalgic look at something warmly remembered.

NANCY EINREINHOFER